The world guide to rum

Where does rum come from?

In his book, Rum, a Social and Sociable History, Ian Williams calls rum "the global spirit with its warm beating heart in the Caribbean."

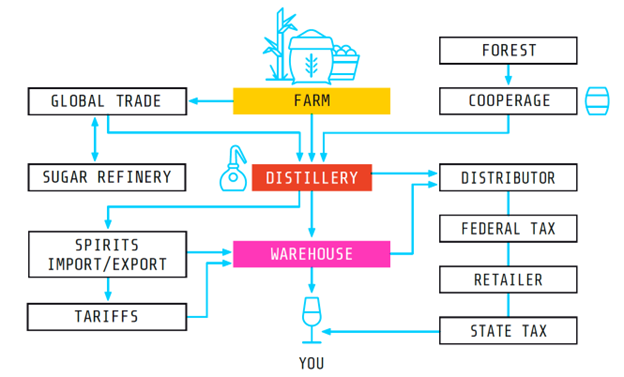

Dreamy metaphor aside, most rum styles are legacies of former Caribbean colonies, but that "warm beating heart" also pumps rum and raw materials to just about every country in the world. In fact, it can be impossible to tell from the label where exactly your rum came from, and plenty of brands sell domestic and imported distillates blended together, which is extra confusing when the brand clearly isn't based in a sugar producing region.

To cut the complexity, we like to focus on raw materials. How you source your fermentable substrate not only drives the characteristic flavors and aromas of your distillate, it also speaks volumes about your attention to ethics, sustainability, and quality. To understand rum as a global category, it is important to understand how rum is made and marketed, all the way back to the cane field.

Alcohol is made from sugar. Full stop.

Fermentation is where all the most interesting things happen in foods and beverages—ingredients get more edible, less spoil-able, tastier and…alcoholic. For distilled spirits, wine and beer, this happens because plant sugars (mostly, there are some animal-derived products out there) are introduced to yeast, single-celled microorganisms of the fungus kingdom, that consume sugar and excrete alcohol and carbon dioxide (their literal waste is our gain).

Sometimes it's yeast that lives in the air or on grain, cane, or fruit that provides our favorite psychoactive social lubricant, alcohol. Sometimes lab-cultured yeast ensures a cleaner, more controllable ferment. Either way, if you play your cards right, you get an alcohol solution ready to consume as-is. With a little more work, you can also distill a "spirit" and toast the ancient, alchemical, quasi-religious, and essentially agricultural tradition of preserving your crop as a high-proof alcoholic beverage.

There's no way around the fact that alcohol is agricultural. Whiskey is malt. Calvados is apples. Vodka is potatoes, or grain, or even milk. Distilling alcohol from these raw materials is the agricultural equivalent of putting your hard-earned savings into gold: it's value dense, shelf stable, and there’s a good chance you can sell it in a pinch. Distilled beverages have been around since at least the 12th century. In fact, distillation technology is so pervasive that you could hardly find a more prototypical science by which to trace the development of modern technology and society.

Rum is the spirit we make from the best sugar source we've ever found.

Rum is made from sugar cane (and its byproducts), a crop that was just getting traction in Islamic southern Spain in the 12th century, and one that Christopher Columbus brought to Hispaniola on his second voyage. Almost without exception (sugar beets are a modern development), sugar cane is the most efficient and available source of sucrose, and for this reason is the world's largest agricultural crop.

Sugar cane is huge because there's so much more available sugar to be had per ton of sugar cane than any grain or fruit, and it’s so much more available. For example, a whiskey distiller needs enzymes to first unlock the long-chain carbohydrates in wheat, rye, or barley starch in order to access the sugar. When it comes to sugarcane, it’s all right there in the juice.

This all adds up to a highly profitable agricultural commodity, so lots of folks get into the business of processing sugar cane and its downstream, value-added products, including rum.

Depending on how it's processed, you can coax some really complex and funky rum flavors from your cane. Fun! But first, where does sugar cane come from?

Where does sugar cane grow, and how did it get there?

The tropics and subtropics are the only places where sugar cane is grown at commercial volumes. It's no coincidence that these are also the parts of the world most changed by early modern colonial globalization. Portuguese traders first pioneered sugar cane agriculture as a scalable colonial enterprise in Goa, India, later honing their skills in Brazil. Later adopters of sugar cane processing technology (and labor practices) included British and Dutch settlers around the Caribbean, and especially in Barbados.

Because sugar cane is an intensely laborious crop, optimizing labor margins has always been part of the business. Indentured European labor quickly became too expensive for early colonial planters, so wholesale xenophobia, violence, and coercion was quickly tapped to establish cheaper labor pools. The Guanches, indigenous inhabitants of the Canary Islands, were among the first victims of vicious sugar cane economics. The European appetite for chattel slavery was whetted in these early colonial days of the sugar industry, and enslaved African labor quickly became integral to the sugar plantation business model.

The success of sugar cane agriculture around the world was, and is, a study in global capitalistic extremes. A voracious global sweet tooth drives demand, hyper-capitalist profit optimization requires the cheapest labor, and this strange perennial plant with extraordinary sugar content is now the world's largest commercial crop.

What is it like to cultivate sugar cane?

Sidney Mintz, in Sweetness and Power, a history of sugar production and consumption, cites three major factors of early Caribbean sugar production that set it apart from other agro-business ventures of the day. First, a successful sugar enterprise needed both agriculture and industry, field and factory, under one "roof". Growing the cane is only half the story: pressing, boiling, and crystallizing the juice are also necessary activities to capture value from the harvested raw materials. Second, a large labor force of both skilled and unskilled workers was required, and third, timing is everything with sugar cane. Multiple plots planted and harvested serially throughout the year ensured a constant supply of cane to the mill, and post-harvesting operations were executed with alacrity to avoid aggressive spoilage. With a large workforce performing many different tasks under extreme time pressure, discipline, says Mintz, was paramount.

In modern fields, the cane is worked both by hand and machine. U.S.-grown cane is mostly harvested by machine, but where labor is cheaper, cane is still tended and harvested using machetes and other hand tools. Whether by hand or machine, it's usually done by planting "billets", short sections of budding cane stalks, and then tending, fertilizing, irrigating, and eventually cutting canes for transportation to a mill. To the average rum connoisseur, whacking at cane with machetes is probably the most recognizable manual labor associated with their favorite tipple, but there are many other very physically demanding tasks required over the 9–12-month growth cycle between harvests.

Once at the mill, cane is quickly pressed and the juice clarified before it undergoes a series of boiling and crystallization processes, each resulting in different gradations of molasses and sugar. Historically, recovering the sugar from cane juice was managed by highly specialized workers, often brought in from other sugar producing regions. The modern procedure for boiling and crystallization is remarkably unchanged from even the earliest techniques, with complex requirements for heating, cooling, and timing the boil now managed by more specialized equipment.

The dependence on a large and cheap labor force alone is a clue to one of the more problematic aspects of modern sugar (and therefore rum) supply chains, i.e., your moderately priced bottle of rum may well owe its reasonable price point and fat distribution margins to underpaid, exploited field workers. Also, because of the vastness of commodity sugar production, transparency is difficult, although recent import bans suggest that U.S. policymakers are getting some insight into the global sugar industry.

Different sugar cane products make different kinds of rum

You can’t just load up a container of cane juice and ship it across the Atlantic. The result would be a smelly, sticky, fermented time bomb. Oxidation and spoilage are very aggressive because sugar cane juice is loaded with sucrose, so it has to be processed very close to the place it was grown, or preserved somehow for travel and processed elsewhere. Cane juice can take different paths before it gets turned into rum, and each path results in a different style.

- Molasses rums: First, cane juice can be processed into refined sugar, with the resulting molasses byproduct either fermented and distilled on site, or sold for rum production elsewhere.

We love molasses rum, as the nutrient-laden raw material is very yeast-friendly and can produce a wonderfully rich flavor profile. Also, molasses is incredibly shelf stable and can be shipped anywhere in the world without concern for spoilage. Because commodity sugar and molasses supply chains are difficult to trace back to their source, the ethics, sustainability, and even quality of this raw material can be difficult for a rum producer to assess. - Cane juice rums: The highly perishable cane juice can also be used to make rum directly. Rhum Agricole, a product of Martinique and Guadeloupe, is one example, but there are many others. Depending on the style, fresh cane juice can be processed directly, or, in some cases, it can even be frozen for transportation to distilleries around the world, although this has obvious logistical challenges and added costs.

Rum made from fresh cane juice can have wonderfully funky, grassy, and vegetal aromas, and if there's any spirit that we might argue is terroir-driven, cane juice rum is it. Unprocessed cane juice carries with it all the dirt and grime from the field right into the fermenter. If that's not terroir enough for you, we're not sure what is. - Cane juice syrup rums: In a borderline case, the cane juice can also be boiled into a shelf-stable syrup without crystallization or separation of sugars. The syrup can then be stored by a distillery for processing after harvest, or even shipped globally for distillation elsewhere. This type of usage results in not quite a cane juice rum, and not really a molasses rum. Interestingly, small producers looking for less ethically murky raw materials often opt for this category both because of traceability and reliability.

- Sugar wash rums: In the U.S. and other large spirits markets, you can also make and sell rum distilled from fermented refined sugar products ("wash" = batch of fermenting liquid), up to and including white table sugar. Evaporated cane juice is one example of this. Because these refined raw materials are all concentrated sucrose with not much left of the original juice, rum from refined sugar is often less characterful. All of the ethical and quality quandaries of molasses are present in this raw material as well. But it's cheap and easy to ship, store, and work with, so there are lots of sugar rums out there.

Rum styles by region (alphabetical).

Generally speaking, the most established rum styles have either a direct geographical connection to the place where the cane is grown, or an indirect colonial connection via raw materials trade routes. It's not always possible to establish a flavor profile based on raw materials sourcing, but the relationship between region and raw material is a great place to start when you're trying to understand rum as a category

We’ve put together a kind of internet "pocket reference" to the ideological segments in the "rum world", as seen from both from the consumer standpoint (connoisseurship) and from the producer standpoint (branding), and grounded in where the raw materials come from.

Getting to know this list is not only a great way to discover the rainbow of rum styles from around the world, but also to appreciate the many geographical and cultural ties (or disconnects) that inevitably arose from colonial supply chains.

Barbados

It's only at the top of the list by alphabetical coincidence, but Barbados could be described as the historical seat of rum. Due to its upwind position from most of the other Caribbean islands, Barbados was relatively inaccessible during the heyday of European territory jockeying in the region, so the English colonizers who set up camp there were more or less left to their own devices for a long time. This relative stability, and the suitability of the island for cane cultivation, helped make Barbados an early titan of the sugar industry, and Bajan (BAY-jun) rum is still a respected and distinctive local style.

Sometimes referred to as "Barbados water", smooth, expressive, big-bodied, aged modern rums from this island are still made from locally produced molasses, and there is a long-standing tradition of expert blending due to a funky 1906 law that prevented the sale of rum in quantities under 10 gallons. This all but prohibited direct-to-consumer sales (sound familiar?), so blenders stepped in to bottle and sell under their own labels. Barbados rum is currently produced at three distilleries which supply a good deal of rum to the bulk market and also bottle some coveted super premium releases in-house for worldwide consumers. Barbados may not have the market share it once did, but it is still an important, respected, and influential player in the rum industry.

Brazil (cachaça)

Brazil is the largest sugar producer in the world, and its national rum-adjacent beverage, cachaça, is made from domestic cane juice under Brazilian and reciprocal U.S. laws (the regulations differ in the EU). Known for its fruity esters and herbaceous cane juice aromas, cachaça doesn't have to meet too many regulatory requirements, and both sugar and caramel coloring may be added post-distillation. The end result varies widely in flavor, sweetness, and overall quality. Aged cachaça matures primarily in oak barrels, although barrels made from a variety of indigenous hardwoods are also used to impart distinctive flavors. Most cachaça is sold domestically in Brazil.

Central America, Columbia, Venezuela:

It's a bit reductive to lump so much geography into one stylistic category, but there are many similarities in rums from these regions that are available in the U.S. market. Rums are made from both fresh cane juice and molasses and are known for their cane ester qualities, with an oak character that is more pronounced than Cuban rum. Often there is a smooth texture created by the addition of sugar post-distillation.

Cuba

All Cuban distilleries are state-owned, and historic isolation from the U.S. market after the Cuban Revolution ended is a huge part of what makes Cuban rum its own style. Production is complex and highly regulated, with a fascinating collective of maestros roneros managing and maintaining the style. All raw materials, primarily but not exclusively molasses, must be Cuban in origin and a system of filtering, aging, blending, and re-barreling help to create Cuban rum’s distinctive lighter flavor profile. No additives or flavorings may be added, and rums are often aged in very used oak barrels (not much wood extract left). Sugar may be added post-distillation and the final product is sold both aged and unaged. The Cocktail Wonk describes Cuban rum as “...light, elegant and refined…Their rums don’t come across like the pot-stilled ester bombs of Jamaica and Guyana, nor are they as in-your-face vegetal like young rhum agricole.”

Dominican Republic

Hispaniola, the Caribbean island shared by both Haiti and the Dominican Republic, has a long history of sugar cane cultivation. Columbus brought the first cane seedlings to what is now Haiti on his second voyage, and Spanish planters were well established on Hispaniola at the start of the 16th century, not long after cane was first cultivated in Brazil, making the Dominican Republic one of the older sugar-producing countries in the world. The Dominican Republic also happens to be home to one of the most powerful modern sugar empires in the world, one that has been heavily criticized for unethical labor and agricultural practices, and is currently facing a U.S. Customs and Border Protection withhold release order.

We hypothesize that a focus on sugar exports (Dominican sugar plantations have excellent lobbyists in Washington, D.C.) has resulted in a smaller specialty market segment than other rum producing regions, or at least a quieter nerdy rum blogosphere. There is plenty of Dominican rum sold by three large brands, and there is plenty of third-party bottling.

Guadeloupe, Martinique

Rum from the French Caribbean islands of Guadeloupe and Martinique are referred to as rhum agricole, although technically, rhum agricole is cane juice rum from Martinique and "rhum agricole de la Guadeloupe" is cane juice rum from—you guessed it—Guadeloupe.

Martinique is a protectorate of France, and the words rhum agricole are a French Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée (AOC) that regulates the production of rums from these areas to guarantee authenticity (rums from Guadeloupe are produced under a Geographic Indicator or GI, instead of an AOC, but the effect is similar). Rhum Agricole is column distilled from freshly pressed cane juice, has to be aged in not-too-large wood barrels to ensure the appropriate level of extraction, and several other rules specify equipment and processes similar to those used to make Cognac and Armagnac.

The Cocktail Wonk describes agricole rum as “primal, vegetal, and grassy,” and we agree—agricole rum has a dry sugary funk all its own, and is vastly different from many molasses-based rums. Some high ester marks (distillates) are also made from molasses to create a style called "grande arôme". These rums are similar to the Jamaican products and are valued by blenders for their intense flavors and ability to spice up a blander base spirit.

Guyana

Guyana once had a thriving rum industry along the fertile Demerara River, a name still globally associated with high quality specialty sugar. Dutch and later English settlers built stills to make use of all the leftover molasses. For a long time, these distilleries produced rum for the British Navy, defining a longstanding blended category. That all ended in 1970 after someone figured out that drinking on board might not be the wisest policy, and shortly afterward Guyana’s rum industry was nationalized. Distilleries began to dwindle. Now just one distillery creates highly coveted and distinctive rums from local molasses, much of it on legacy equipment from long-closed distilleries (to much nerdy delight). As with other rum producing regions, high ester marks are favored by blenders, and international clients buy bulk for third party bottling (like us! Check out our Bulk Rum).

Haiti

Haiti doesn’t produce much rum for the global market, with only one brand commercially available outside the country for some time. A number of very small distillers produce cane juice rum, called clairin, for local markets that is mostly consumed unaged. According to Shanika Hillocks, clairin highlights heritage sugar cane varietals and wild yeast ferments. There are many styles and expressions of clairin produced by hyper-local distillers, only some are available in export markets. Clairin entered the U.S. market as rum's answer to mezcal, and there are similarities (ultra-small artisan producers, limited availability, made without mechanization). Issues have been raised by spirits industry activists highlighting unequal representation, labor fetishization, and unfair power dynamics between Haitian producers and European brand owners as these lesser-known spirits are hyped to a receptive global market.

India

Goa is the birthplace of modern sugar cane agriculture, but you may not have tasted an Indian rum before. Even though India is the second-largest producer of sugar cane globally, and a great deal of rum and spirits are made from domestic molasses, most of it stays in India. This is in part due to India’s spirits labeling laws, which vary widely from the laws in the major potential export markets (Europe and the U.S.). For example, neutral spirits distilled from molasses and blended or flavored may then be sold as whisky, which makes for tricky export into markets where, for example, only grain can be used to make whisky. However, India now has solid representation in the global single malt whisky category, and there are some rums that adhere to international labeling and production standards available.

Jamaica

Jamaica produces world-famous rum from local sugar cane, including rums made with molasses, fresh cane juice, and sugar cane syrup. "Hogo", derived from "haut goût" (an archaic reference to the desirable funk of aged meat), is a term used since at least the 18th century to describe Jamaican rum’s signature funky, fruity, and spicy aromas and flavors. The highest ester distillates are avidly sought after by rum blenders globally who can purchase a small amount of Jamaican rum and blend it with cheaper, high-volume domestic spirits to good effect. As in other rum styles, Jamaican rum is often distilled in a double retort pot still, but the still design only enhances flavor characteristics derived from fermentation, including from the famous use of dunder and muck. Jamaican rum is sold both aged and unaged.

Japan

Japan may be an outlier when it comes to rum production, but the Japanese have cultivated sugar cane since it was brought to Japan by the Chinese in the 17th century. Rums distilled from both local cane juice and molasses are gaining popularity domestically and internationally, and comparisons have been made to a number of Caribbean styles, although there are also brands that might be closer in flavor range to the Japanese shōchū category. Rums are sold both aged and unaged.

Mauritius

The island of Mauritius has seen a succession of European powers claim its shores, from the Dutch in the 17th century to the French in the 18th century and finally the British in the 19th century. Each wave of colonization expanded sugar cane production on the island, although rum from fresh cane juice was long prohibited to protect sugar exports. When the ban was lifted in 2006, local distillers began producing rums with fresh cane juice which is sold both aged and unaged.

Philippines

The Philippine islands were colonized first by the Spanish in the 16th century, then by the English in the 18th century, and finally by the United States in 1898, when Spain released its claim to the islands after strategic losses in the Spanish-American War. The Philippines did not gain independence until the signing of the Treaty of Manila in 1946 at the close of WWII. That is a long, complicated legacy of colonial influences to grapple with.

While prehistoric indigenous groups in the Philippines cultivated sugar cane, it was Spanish colonists who cultivated cane as a both a domestic and export commodity. It wasn't until the late 18th century that international (primarily American and British) demand for sugar and molasses led to a boom in Filipino sugar production, but rum made from either molasses or fresh cane juice stayed mostly within the domestic market. That may be why international rum nerds are surprised to learn that the Philippines, along with India, are responsible for 41.6% of global rum sales.

While there are several rum distilleries in the country, Filipino rum is dominated by one brand, Tanduay. Rum is sold both aged and unaged, and generally distilled on column stills.

Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico was long a major U.S. supplier of cane sugar until sugar beet cultivation took hold in the early 19th century, and molasses byproducts were put to use in increasingly efficient, high-volume rum production facilities. Because the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico is an unincorporated territory of the U.S., it has direct access to the U.S. market, which at least partially accounts for a focus on high volume production. Puerto Rico also benefits from "cover-over" rebates, which are essentially bill-backs on federal rum excise taxes. These two features have likely skewed the Puerto Rican rum industry towards efficient production of light distillates for massive bulk and bottled export.

Puerto Rican rums are required to be aged for a minimum of one year, though the aging is not typically done in barrels and the result is still clear and light bodied. Puerto Rico produces large volumes of this silver rum along with amber and gold rums, some of which are combined with caramel coloring to mimic the oak tannins of barrel aging. Rum is sold both aged and unaged.

There are some distillers on the island making smaller-scale, more complex molasses-based rums. This experimentation has resulted in some coveted small batch releases of varying styles.

Suriname

The Republic of Suriname was a part of the Dutch colonial empire until it was granted independence in 1957. Originally, Suriname was a valuable sugar producing colony for the Dutch, but sugar production diminished as trade commodities like valuable minerals and ore gained dominance. Rum is produced in Suriname, although political instability in the 1980s stymied industry growth. Rums from this region are still not widely available in the U.S. market, but they are definitely getting the attention of rum nerds looking for new and interesting products.

Trinidad and Tobago

At the turn of the 18th century, Spain had invested a lot of money in sugar plantations and very quickly turned over control to the British, who continued cultivating sugar cane in Trinidad and Tobago. Three major rum companies emerged, but a familiar story of market pressure, consolidation, and re-privatization ensued, resulting in only one remaining distillery in Trinidad producing world-famous bitters, a handful of aged and unaged house bottlings, and a whole lot of bulk rum for export. Molasses used to be domestically sourced, but it's imported from places like the Dominican Republic and Fiji now. Stylistically, rums from this region have more in common with a Cuban rum than a Jamaican rum, despite common British colonial history, with blending, aging, filtering, and added caramel all playing a role.

United States

If we had to pin down a style for U.S. rum, we'd call it "emerging." As you'll see below, several states are making rum from U.S.-grown cane juice and from a variety of raw materials both imported and domestically produced, but U.S. contributions are a tiny, recent blip on rum's epic timeline. A cohesive American style has yet to develop, except perhaps in the case of the relatively extinct New England rum, which has old ties to the colonial rum trade.

Fun fact: It's not by accident that rum lags behind the bourbon boom in the modern U.S. market. While New England colonists were by all accounts very accomplished rum drinkers, it was for practical reasons: grain was often in short supply and cheap Barbados rum was readily available. According to Ian Williams, "it was with famine and profit in mind" that distillation of grain ferments was even outlawed in some places.

Already chafing under British rule, colonists were outraged when they were hit with the Molasses Act of 1733 and the Sugar Act of 1746, economic kicks in the gut to an economy that had grown dependent on bartered (and quaffed) rum. By the end of the Revolution, Americans found themselves economically ostracized from the West Indies, and domestic whiskey already accounted for one third of American spirits consumption. Politicians then turned on rum, emphasizing domestic grain and corn whiskey (and domestic whiskey excise taxes!). Tavern-goers who once drank 3 pints of rum a week began whetting their whistles with a more patriotic spirit. It would be a few centuries before our modern bourbon boomed, but rum never recovered.

- New England rum: If New England rum has a style, it's a historic nod to the early colonial days of distilling rum from imported Caribbean molasses. Distillers aiming to recreate the style aren't uncommon, and there is at least one distillery garnering lots of respect from the rum nerds.

- Hawaii: Sugar cane has been grown and cultivated in Hawaii for centuries, according to some Hawaiian distillers. Hawaiian rum brands distill locally grown cane juice and molasses to produce some excellent silver and aged rums, but the last days of sugar refining in Hawaii are over, so future molasses sourcing is uncertain. Driven by a few of the smaller boutique producers, there may well be a Hawaiian cane juice rum style evolving.

- Louisiana: Louisiana is growing cane for U.S. distilleries that are distilling rum from fresh cane juice at a local plant, freezing the cane juice for transport, or boiling it into syrup to preserve it for off-season processing. There are several distilleries, but there's not really a regional style to speak of.

- Alabama: Cane is certainly grown here, and at least one distillery that we know of is distilling rum with local cane juice.

- Florida: Several distilleries in Florida are making rum from fresh local cane juice as well as imported molasses. Expressions vary, and there's not really a regional style as of yet.

- Other U.S. states: there are plenty of folks making rum around the U.S., check out our article on interesting domestic cane juice and molasses rums. But again, there really isn't a regional style to point to, especially without a local history of growing or importing cane products. No disrespect! We're just looking at the supply chain from the bottom up.